Maximum Independent Set on Unit Disk Graph

In this post I’ll share a practice exercise I got from my CS 4540 class at Georgia Tech and my solution to it.

The Problem

In the Maximum Independent Set on Unit Disk Graph (MISUDG) problem, we are given a set \(S\) of unit- diameter disks in the plane. The goal is to find a maximum-cardinality subset \(S' \subset S\) of disks, such that no two disks in \(S'\) overlap. (We say that disks that only touch on the boundary do not overlap). As with the Maximum Independent Set problem, this problem is also NP-Complete.

- Consider the following greedy algorithm: start with \(S' = \varnothing\) and process the disks in S one by one, in any order. For each such disk \(C\), if \(S' \cup C\) is a feasible solution, then add C to S′. What is the approxi- mation factor of this algorithm? (Give the best upper bound you can.)

- Let \(0 < \epsilon < 1\) be some constant. Assume that we are given a grid whose lines are spaced \(\dfrac{1}{\epsilon}\) units apart. Assume further that no disk in the input set S intersects the grid lines. Give a polynomial time algorithm for solving the problem exactly in this case.

- Derive and analyze a PTAS for the MISUDG problem. Hint: Consider a grid with random offset: Take a grid of lines spaced \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) apart, such that the origin is at the intersection of a horizontal and vertical grid line. Pick a shift/offset \(L\) uniformly at random from \([0, \dfrac{1}{2})\), and shift the grid vertically and horizontally by an distance \(L\). (Equivalently, consider the grid of spacing \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) such that the point \((L, L)\) is at the intersection of two grid lines.) What is the probability that a disk is intersected by a grid line?

Observe

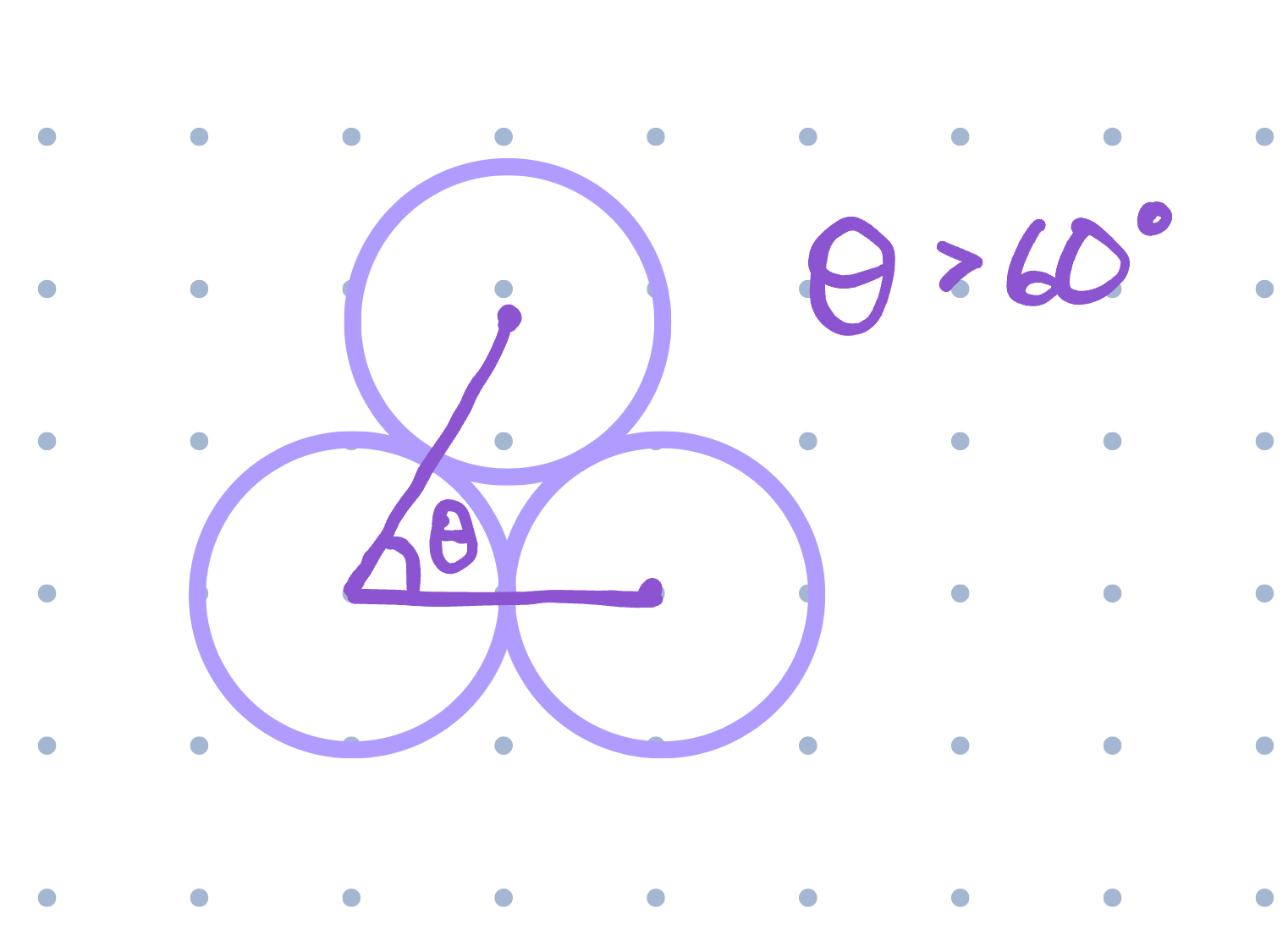

We start out by noticing that for a disk \(x\), the maximum number of independent neighbors is 5. This is because each neighbor must intersect \(x\), and the angle between the centers of neighbors must be greater than \(60^\circ\). If \(\theta \leq 60\) then the neighbors would intersect eachother and wouldn’t be independent anymore, a contradiction. Since there are \(360^\circ\) around \(x\), we have:

\[360 = n (60 + \delta)\] \[n < 6\]

This means the maximum number of independent neighbors for any given disk is \(5\).

Solution to 1

The greedy algorithm doesn’t choose disks in any particular order, so we choose the order it uses in the worst case scenario. Notice for disk \(x\) with \(5\) independent neighbors, 2 maximal solutions would be either just disk \(x\), or all of the \(5\) independent neighbors. (None of these neighbors intersect each other, so they would form an independent set.)

Let \(C^*\) be the largest independent set. For each disk \(d\), the worst possible case would be if instead of choosing \(d\), we chose its (up to) \(5\) independent neighbors. Let \(C\) represent the greedy solution. So, we have \(|C| \leq 5 |C^*|\). This means greedy is a \(5\)-approximation of the optimal algorithm.

Remark

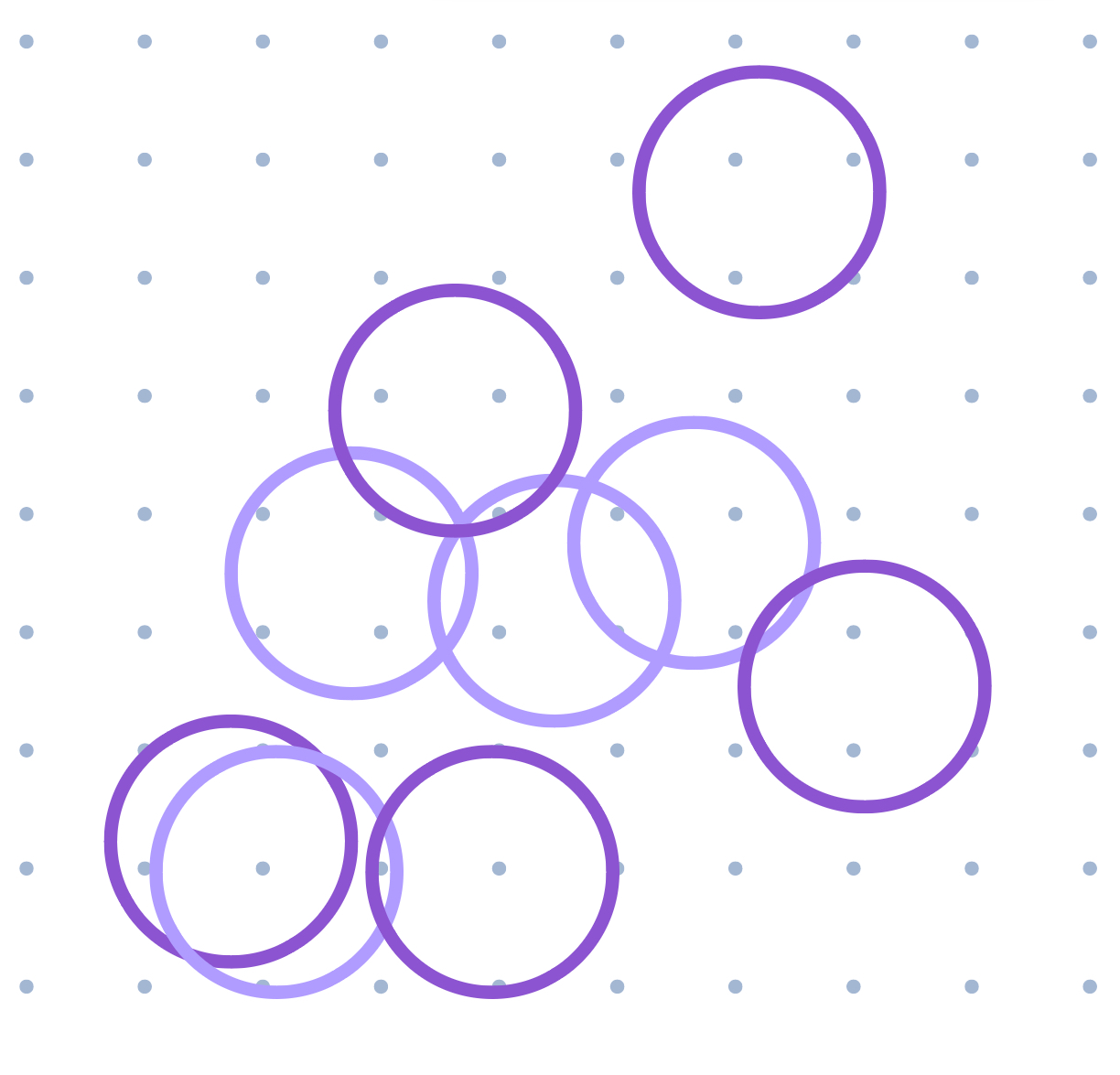

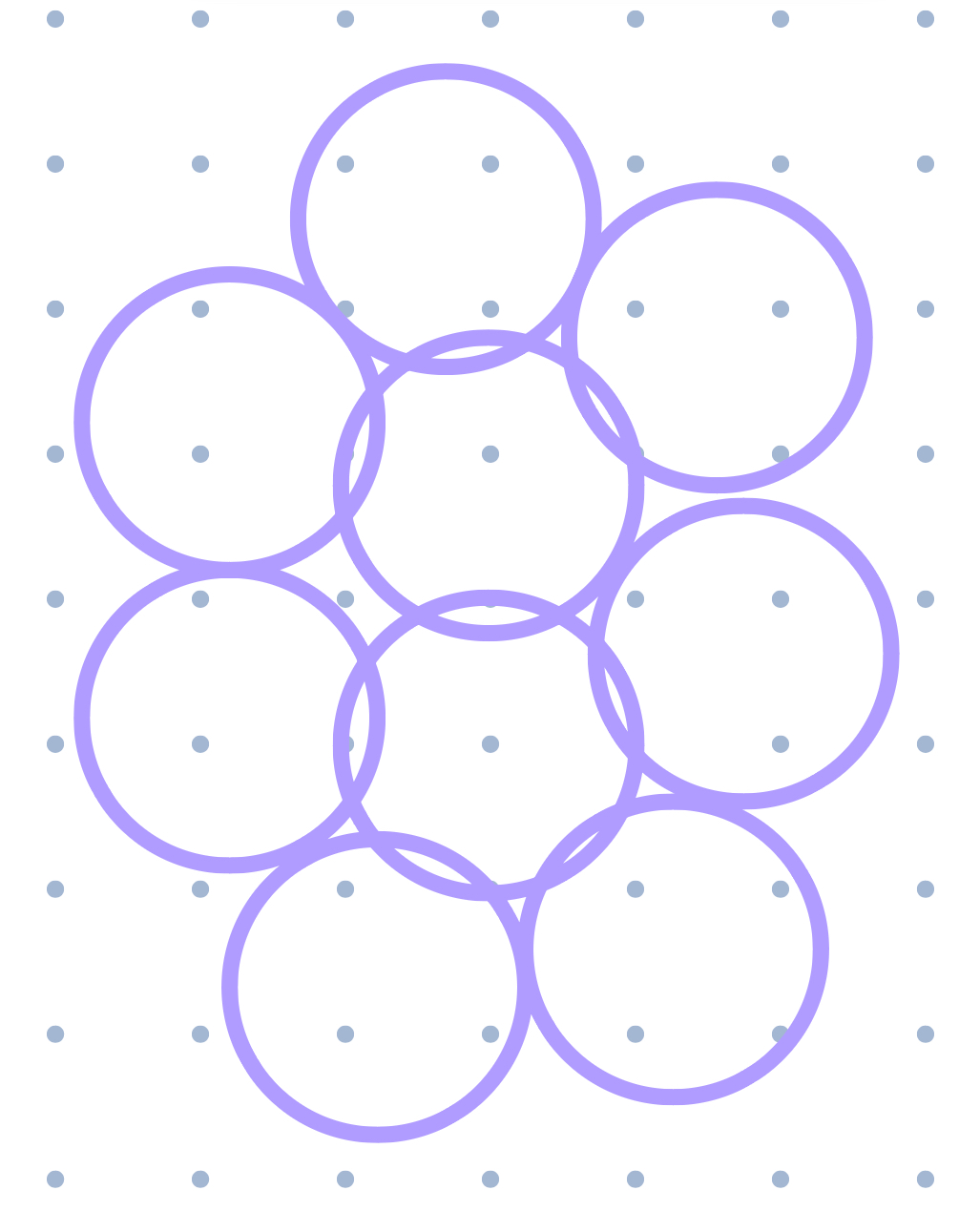

Realistically, the actual approximation is a little better for larger input sets, since apart from this trivial case, not every disk in the optimal solution is surrounded by \(5\) independent disks. See the following picture for reference.

Solution to 2

I thought this solution was pretty cool: we know independent set is NP-complete, so we can’t just convert to a graph and solve. Instead, we do a crazy brute-force algorithm.

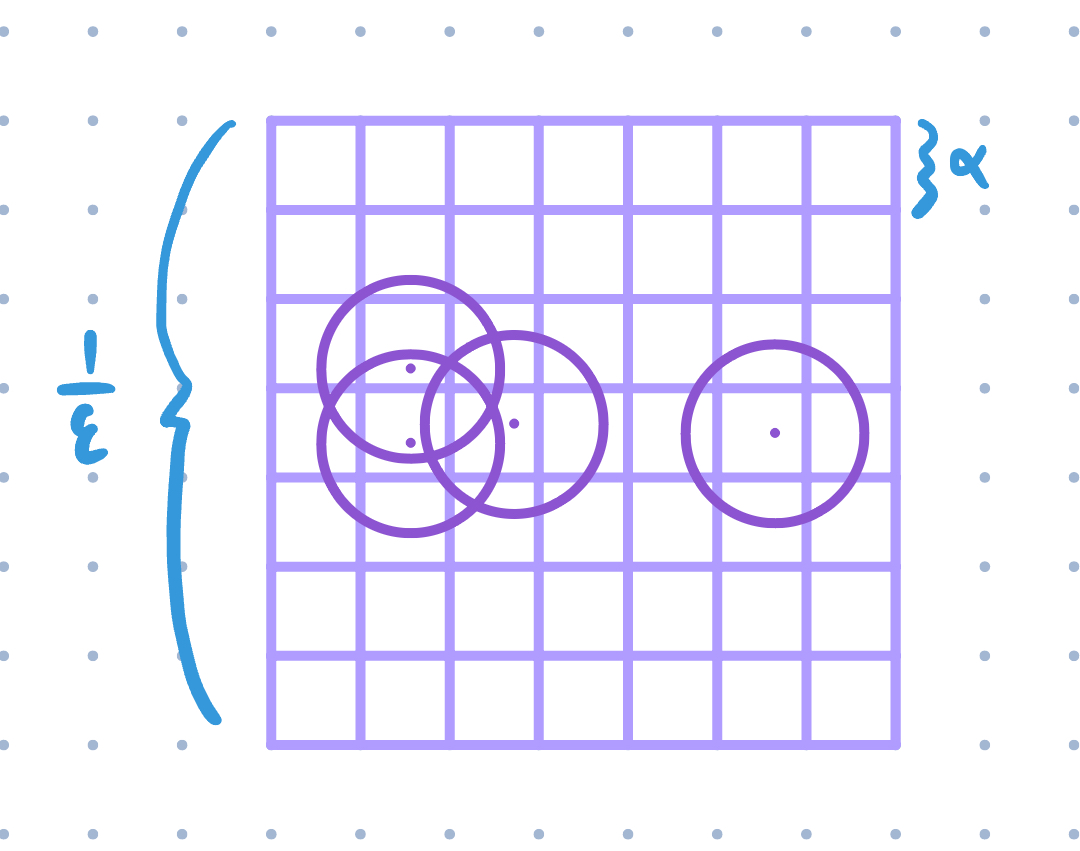

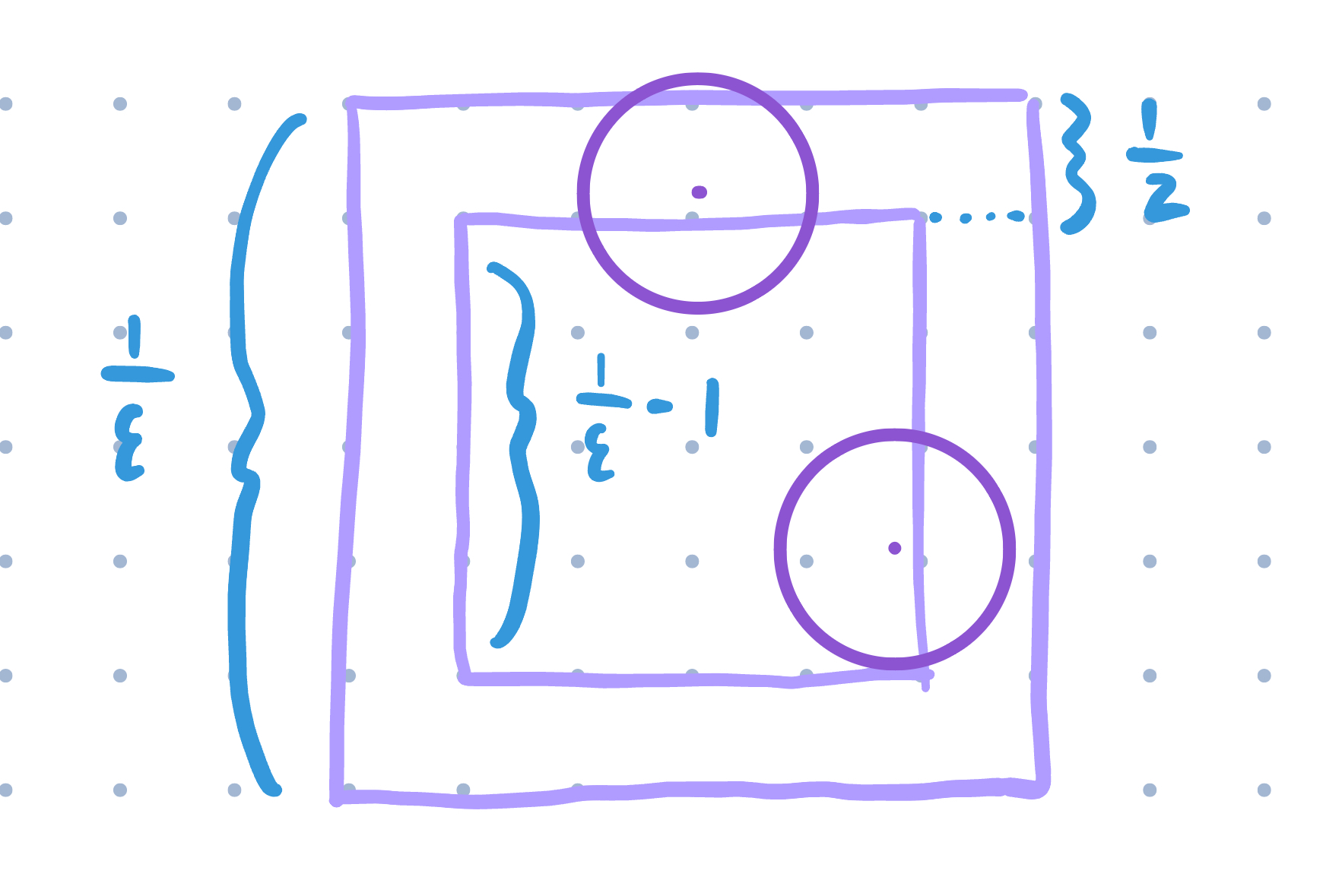

Consider a single grid square of size \(\dfrac{1}{\epsilon} \times \dfrac{1}{\epsilon}\). We split up this grid further into squares of size \(\alpha \times \alpha\). Each smaller square we assign the set of disks whose centers are contained within that square. (As an edge case, if a center is on the boundary, we just assign it to one of the squares.)

As long as we choose \(\alpha\) such that we can’t fit 2 disks next to each other without them intersecting in an \(\alpha \times \alpha\) square, we know at most 1 disk contained from this square will be in the independent set. (Since if there were 2, then they must intersect eachother, and therefore it wouldn’t be an independent set anymore) We can choose \(\alpha = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt 2} - \delta\) since the longest distance in a square of side length \(\alpha\) is the diagonal of length less than \(1\). If there were a disk on opposite corners, they must intersect since the radii are \(0.5\) but the distance between centers is less than \(1\). (We can set \(\delta=0\) for the purposes of the rest of the problem)

The actual independent set will contain 0 or 1 disk from each square–we know this because disks can still intersect across the little square boundaries, meaning we choose a disk from one little square but not the other. From this we can make a polynomial-sized list of candidates: we get every combination of 0 or 1 disk from each smaller square. At most, there are \(n=|S|\) disks per smaller square. (Because what if all disks were in one square) There are \(\dfrac{\dfrac{1}{\epsilon}}{\alpha}\) smaller squares per side of a larger square, giving us \(\dfrac{1}{(\epsilon \alpha)^2}\) total smaller squares per larger square. This means there are at most \(n^\dfrac{1}{(\epsilon \alpha)^2}\) candidates to look through. (We just take the number of combinations of the max number of disks in smaller square)

As large of a polynomial this is, it is still a polynomial, and we can loop through each candidate to check if it as an independent set, and find the largest one among those which are. This is a polynomial way of getting the independent set for one square–we know the max independent set will be the union of all the max independent sets of the grid squares. (Since no disk can intersect across larger squares, we don’t have to worry about trying each candidate!) Thus we have a polynomial time algorithm to give us an exact answer!

Remark

Theoretically, and perhaps impractically (although this entire solution is impractical) we could do away with the larger grid and solve the entire problem exactly using the smaller grid squares. This would result in a much larger polynomial than we already had, but would still work. Also, the big grid square probably won’t divide \(\alpha\) evenly. This is fine, as we only really care about being able to iterate over space (which is polynomial) rather than vertex combinations (which is exponential).

Solution to 3

We make the bigger grid and shift it by \(L\). We remove each disk that intersects a bigger grid line, and run the algorithm outlined in part 2 on this new set, giving us an approximation of the independent set. For the approximation ratio, we consider which disks we remove (which disks intersect the grid line).

If disks are within \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) of the grid line for a given grid square, then it will be removed. Our approximation only uses the ones that aren’t within \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) of the grid lines, or those that are within a \(\dfrac{1}{\epsilon} - \dfrac{1}{2} - \dfrac{1}{2}\) square inside the square. If we assume the disks are in a random position in the square, the probability is the area of the inner square minus the area of the outer square, which is the following

\[\dfrac{\left(\dfrac{1}{\epsilon}-1\right)^2}{\dfrac{1}{\epsilon^2}} = \dfrac{\dfrac{(1-\epsilon)^2}{\epsilon^2}}{\dfrac{1}{\epsilon^2}} = (1-\epsilon)^2\]We are allowed to assume the disks are in a random position (relative to the grid lines) since we shift the grid by a random offset \(L\). If we didn’t shift it, an adaptive offline adversary would be able to “set” the inputs to only disks that intersect the grid line, for example, which would return an independent set of size 0. Obviously, this isn’t a very good approximation!

So, this algorithm is a \((1-\epsilon)^2\) polynomial time approximation scheme for MISUDG!

The End

Thanks for reading! If you spot any mistakes (which are likely, this is unedited and kinda unchecked) then please feel free to reach out to me or fix them yourself on github issues. Or, if you have any insights, be sure to let me know!